I’ve recently came accross a very interesting blog post, detailing how the author was able to speed up their Rust compilation by adding his Terminal app to the macOS System Settings Developer Tools, which effectively bypasses apple’s XProtect malware signature checks of executed binaries. He observed that changing this setting drastically improves the rust compiler builds and unit tests execution, because each check by XProtect takes several hundred milliseconds.

You can read it here.

The blog post only looked at the impact for Rust, and left me curios about the impact on compiling a large Go codebase with it. So - let’s try! Also, time to shine some light on the security implications of this, since the original blog post did not dive into that topic at all.

[0x0] Index

- [0x1] Configuration

- [0x2] Compilation

- [0x3] Unit Tests

- [0x4] Security Implications

- [0x5] Conclusions

- [0x6] Resources

[0x1] Configuration

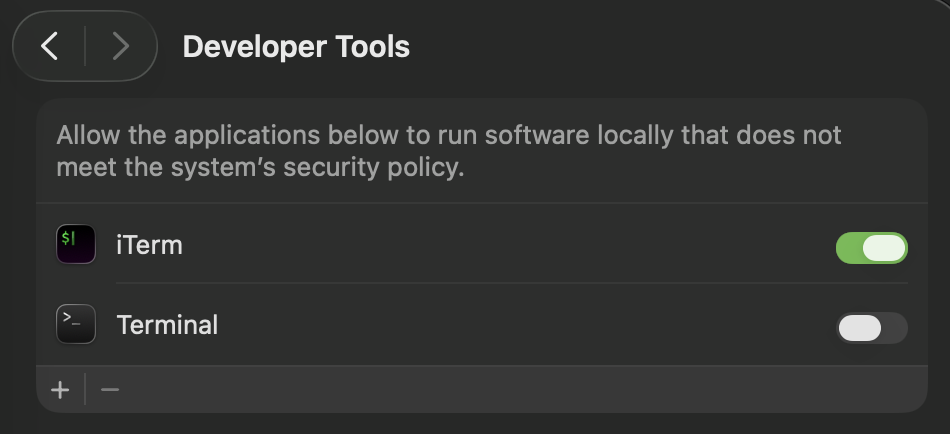

To setup, open System Preferences, navigate to Privacy & Security Settings and choose Developer Tools.

I’m going enable the Developer Tools option for the iTerm terminal app - and leave it disabled for the standard macOS Terminal, to check what’s the performance difference between compiling the same code in the two terminal apps:

[0x2] Compilation

Let’s try to compile my largest open source project with this performance optimization and without and see what’s the impact. It’s a network traffic analysis engine that parses and analyzes huge amounts of network packets in parallel, called NETCAP.

The project conists of around 166k lines of Go source code, has many dependencies and links against two big C++ libraries for deep packet inspection using CGO. So, it’s far from being a simple ‘hello world’ app - and any impact should be noticable.

I’m compiling on a MacBook Pro with a M1 Max CPU.

To prevent the compiler’s caching to interfere with the measurement, I’m running this cache clear command prior to compilation:

go clean -cache

For compiling the project I’m using my build system zeus. It behaves essentially like GNU Make, so don’t worry too much about it.

In iTerm.app (= with XProtect Bypass):

netcap % zeus install

netcap » [1/1] executing install

[INFO] Building with DPI support (nDPI 4.14, libprotoident 2.0.15-2, go-dpi v1.4.1)

netcap » [1/1] finished install in 17.997574333s

In Terminal.app (= without XProtect Bypass):

netcap % zeus install

netcap » [1/1] executing install

[INFO] Building with DPI support (nDPI 4.14, libprotoident 2.0.15-2, go-dpi v1.4.1)

netcap » [1/1] finished install in 20.358332625s

Result: The build without XProtect’s checks was around 2,4 seconds (~ 11%) faster.

[0x3] Unit Tests

Next, let’s see the effects on the unit tests, which consist of 1427 different test functions. Some are testing internal functionality, some are integration tests spin up the entire engine, load a packet capture file for analysis and produce audit record output files on disk.

To prevent the compiler’s caching to interfere with the measurement, I’m running these cache clear commands prior to each test execution:

go clean -cache && go clean -testcache

In iTerm.app (= with XProtect Bypass):

netcap % zeus test

...

netcap » [2/2] finished test in 8m28.4235125s

In Terminal.app (= without XProtect Bypass):

netcap % zeus test

...

netcap » [2/2] finished test in 8m44.113162459s

The result: around 15.7 seconds (~3%) faster.

Given how small this delta is, it’s also within the range where run-to-run variance, I/O jitter, or background activity could matter — so repeating the test a few times and averaging would be the skeptical, statistically safer next step.

But I’m going to skip that. Because bypassing XProtect especially for a developer is a VERY stupid idea anyways. Let me explain why.

[0x4] Security Implications

If bypassing a security mechanism sounds like a bad idea, it probably is.

Not only you are bypassing a mechanism to protect your mac from known malware - aka an infection that could have easily been prevented using a low false positive scan prior to executing the program.

To make things worse, this setting disables the checks for EVERY binary running in your default terminal app. The one that you work in daily. The one that is most likely to be executed in when you are accidentally downloading and running malicious software. Especially for you as a developer, this is an unnessary risk to take.

Yes, that curl | bash command you ran to install that new open source project you wanted to try, but were too lazy to compile from source and check yourself. Or that brew tap from an unknown dev you tried out last week.

So take my advice: don’t do it. The risk is not worth the speedup IMO. Even if the speedup would be 100% or more.

[0x5] Conclusions

Yes, it did slightly speed up my Go builds. Around 11% for a full compile and roughly 3% for unit tests. Nothing extraordinary though - and certainly nothing that would make me rethink my workflow or justify the tradeoff.

The interesting takeaway here is that XProtect’s overhead seems to scale differently depending on the workload. For Rust, which spawns a lot more short-lived processes during compilation, the gains reported in the original blog post were more significant. Go’s compilation model is more monolithic, which explains the more modest speedup. If you’re working with a language or toolchain that generates many small binaries or runs many short-lived processes (think npm scripts, shell pipelines, or certain build systems), you might see a bigger delta. But you’d also be exposing yourself to more attack surface, not less.

At the end of the day, this experiment confirmed what I suspected: the security tradeoff is simply not worth the marginal performance gain. As developers, we are high-value targets. We have access to production credentials, signing keys, internal systems, and customer data. We run code from strangers on the internet all the time - sometimes knowingly, sometimes not. Deliberately weakening your machine’s defenses to shave a few seconds off a build is, to put it bluntly, optimizing the wrong thing.

If you really need faster builds, look elsewhere: upgrade your hardware, move builds to a remote machine, use better caching strategies, or rethink your project’s dependency graph. These are investments that pay off without leaving the door open for the next supply chain attack.

My advice: leave XProtect alone. The few seconds you save aren’t worth the one time it would have caught something.